Every community that I have worked with in creating an artwork has required a different approach. It often depends on the attitudes that people bring to the project, their needs and what they want out of the project. And these can differ from person to person. It’s not a voting system or a horse designed by a committee to create a camel. But it does require constant negotiation, the ability to listen to others and a willingness to debate ideas and a willingness to change. That said, I also bring to the projects my own set of skills, principal of which is in creating an open environment where people feel free to express their ideas, emotions and to try out things that may fail, without the fear of ridicule. My own toolkit contains games and exercises, and a keen sense of what I believe makes good art and an attitude that supports and at the same time pushes a community to show their best work. I am constantly hovering between trying to keep my feet firmly planted on the ground and rooted to facilitation to then wanting to leap in abandonment in the air and join the other performers in play and creativity.

At the core of this process is a strong and long held belief in the importance and need for active and authentic participation in art making, particularly with communities that are under represented politically, socially, economically and culturally in society. I draw on Sherry R Arnstein’s 8 stage ladder of Citizenship Participation (read more) as an inspiration and guide to active and effective involvement at a political, economic and social level in people being able to exercise their power.

When is it Art?

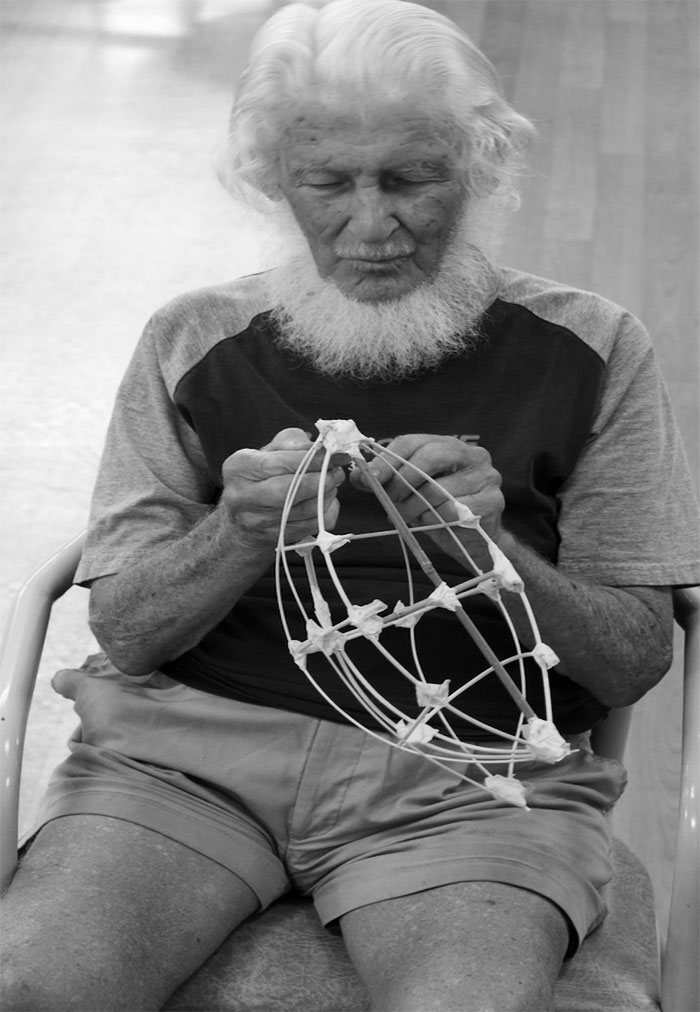

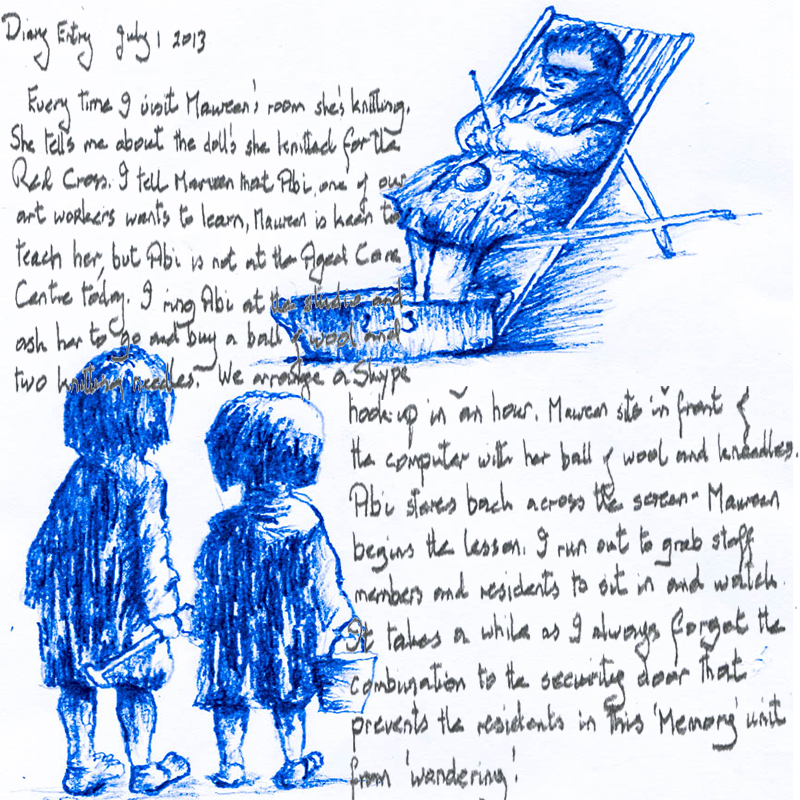

Diary Entry Sept 14 2014

watched Norman begin with a small piece of thin bamboo. He bent it and with a piece of masking tape attached it to another piece of bamboo. This continued until Norman had created the hull of a boat. He covered the framework in paper. Eventually Norman made a mast and a sail. One of the nurses commented that it would look nice placed on top of the piano and displayed in the dining room. Norman had far more ambitious ideas.

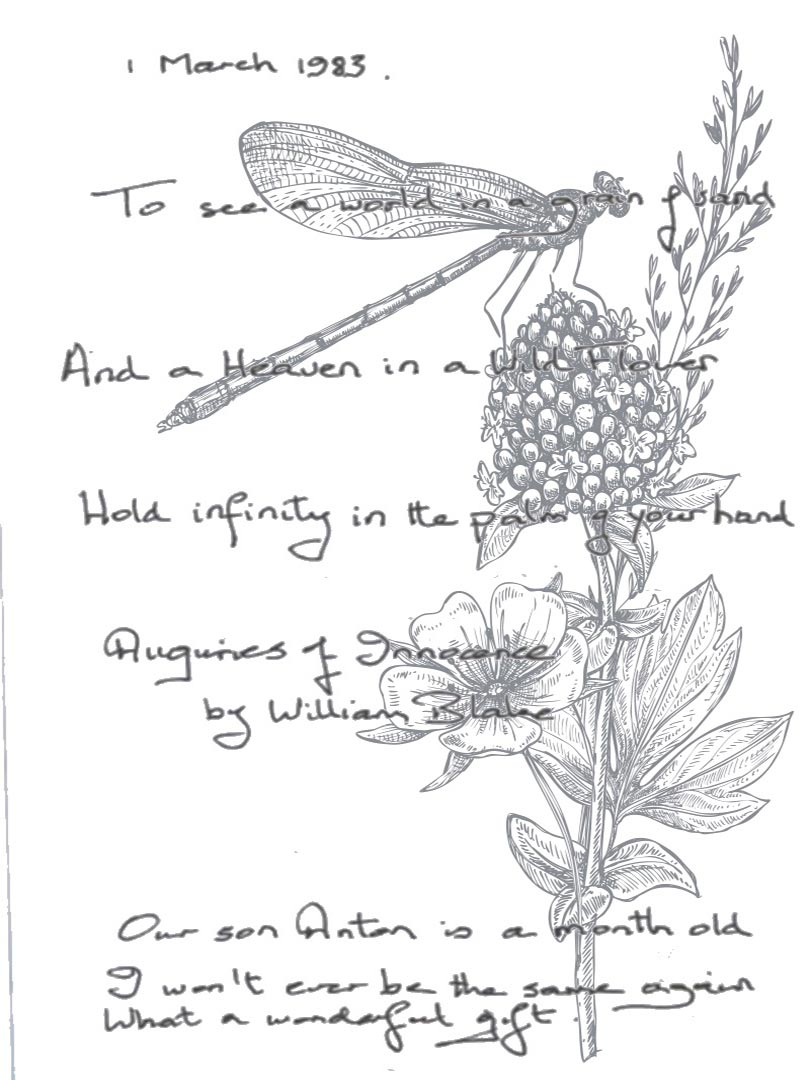

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold infinity in the palm of your

hand

Auguries of Innocence by William Blake

Diary Entry September 15 2014

We workshopped the letters sequence today. While the narration slows down the pace of the show there is a gravity to the content of these letters that draws us into a heightened awareness of what it must be like living with someone who has alzheimers. Being able to put ourselves into the hearts and minds of someone else is another characteristic of art.

” Dear Ben Today was the most terrifying day my life. I shuddered when the doctor said your mother is in the early stages of alzheimers. Not sure where to go from here. I’m reluctant to tell anyone. She keeps telling me over and over that she doesn’t want to be a burden. …..” Love Dad

Diary Entry Aug 1 2014

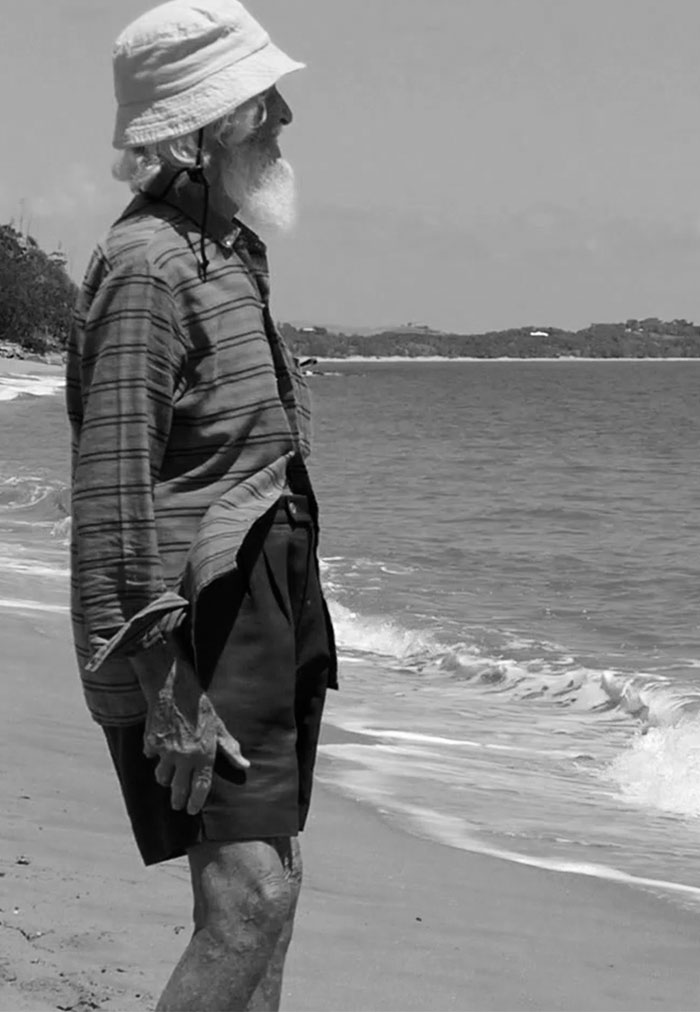

After the workshop, Norman invited Kyla and I to his room. There was a photograph of his wife and a map of the Northern Territory on the wall. Norman told us the story of how he worked with Aboriginal communities in the Kimberleys. Above his bed was a sign that read “the journey is more important than the destination” Little did I realise it then, but Norman’s philosophy of life so boldly emblazoned above his bed would eventually become one of the principle themes of our play, which was yet to be written. One of the qualities of art is being able to take something that is personal and private and adapt it in a way that engages a broader audience. Norman’s story was imaginative and went beyond the personal and literal and touched the audience in a way that was fresh and dynamic. Norman’s boat became everyone’s boat. The sail would eventually transform into a large screen across the lawn of the aged care centre, where moments in Norman’s life were abstracted into swirling colourful shapes. But Norman’s performance was not a solo effort. It’s when he was joined on the voyage to Ithaca by his granddaughter Rosie that Norman’s voyage became something stronger as they depended on each other to get to Ithaka. Norman could have sat down and told us his life story in a very matter of fact way. While this form of storytelling has its place, the combination of dance, metaphor, music, song, imaginative poetic verse and a cast of people of all ages and abilities in front of a live audience made this story extraordinary and took all of us to another shared and insightful level. This was not just about the life of an older person. It was a story of a life lived more intensely with the joy and sorrow that comes with this journey. It was about someone who was passionate about life, part of a larger vibrant community and who was once young like all of us and who became old, like most of us will . This was Art!

Art Making or Therapy?

When Norman Thornton and Woody Tryhorn signed out of the Aged Care Centre on that Sunday afternoon and caught the train to Mackay to join our theatre company they left a way of life and routine they had known for several years. Both spoke highly about the care they received at the centre. They spoke about the activities they did during the day, the tai chi and the arts and crafts, in glowing terms. As they were getting into the taxi to drive to the station, one of the nurses leaned over to me and said “ this is going to be wonderful therapy for both of them.” I’ve never been comfortable with the term therapy. It begins with the idea that there is something that needs fixing, improving or the person needs help. There is a place for it, particularly in aged care centres and a lot of good work is being done for people with Alzheimer’s where the activities are focused on social and health outcomes. It is not however a position or attitude that I bring to these projects. When people share their stories in dance, drawings, theatre, music or photography they are expressing their identity in a way that is distinctly and intrinsically artistic and has the capacity to project ideas and feelings that can be shared, debated and celebrated by others in such a way that the person sharing that tale gains an ascendency in their agency with the world. There is an empowerment process taking place where the person no longer feels helpless. And that empowerment is layered with an abundance of care and love that radiates throughout all of these projects. It’s the attitude of the professional artist from day 1 that will determine whether that sense of empowerment is authentic. Norman and Woody didn’t travel to Mackay for therapy. They didn’t join the theatre to improve their self worth or to alleviate their depression. They came because this was going to be an adventure.

Diary Entry September 19 2004

Pam Huxley, Kyla Ranger and I had been artists in residence at the Hibiscus Aged Care Centre in Gladstone for the past 2 weeks. We lived in a house adjoining the centre. That night I bought 5 salmon steaks and 2 bottles of Sauvignon Blanc and asked Woody and Norman if they didn’t mind missing their dining room dinner and join us at the house. Mid way through the meal I put out the invite.

Steve: “ Why don’t you come to Mackay and we’ll put on a show!”… ..silence…….

Woody: Yeah sure

Steve: I’m serious…you and Norman….

Norman: For how long?

Steve: 3 weeks

Woody: What about our medication?

Steve: We’ll talk to the doctors tomorrow.

Norman: Sounds interesting

Steve: I just need to know whether you think this is utterly ridiculous or there is some slight possibility…

Woody: I need more information.

Steve: I’ve managed to get a 4 bedroom bungalow right on Eimeo Beach. You walk out the back door straight onto the sand

Norman: Keep talking

Steve: You’ll be living there with 2 professional actresses. Ankle McLean is flying up from Melbourne to join the team. Rosie Fyvie is coming up from Brisbane. They’ll be your housemates.

Woody: Interesting.

Norman: What’s the play?

Steve: Not sure. Hasn’t been written yet……this is the way I work ..it depends on your input..ideas and energy…… but that sign in your room…… the one above your bed..

Norman: “The journey is more important that the destination”

Steve: Yeah! Might be a good place to start?

Woody: How do we get to Mackay?

Steve: We’ll catch the overnight Sunlander …and by the way….we’ve got a piano!!

Norman: I’m in!……………….What’s for desert?

Process or Product ?

The sign above Norman Thornton’s bed at the aged care centre in Gladstone says “the journey is more important than the destination” . It became a rallying cry during our research into one of life’s big questions. It led us to Constantine P Cadafy’s poem Ithaka which then formed the basis of our play Finding Ithaca based on Homer’s Odyssey. The ‘process versus product’ argument has always been debated in community arts. Some will argue that it is enough for people to participate in the process and that working towards an outcome is not as important and can sometimes put undue pressure on people and disempower them. I have always steered projects towards a public outcome. I believe that our role as artists is to create opportunities for people to move beyond their own personal activity and to show how audiences will bring their own interpretations into it. The process that leads to that outcome needs to ensure that the participants have a strong ownership of the art and that their contribution to the making of the art is valued and that they are developing new skills along the way. In shaping the material I have always encouraged risk, ambition, inventiveness in ideas and the execution of those ideas that challenges the audience beyond simply offering entertainment.

The journey leading to that exhibition, performance, recital or screening has it’s own processes. Many decisions have to be made: which of your drawings will you exhibit? do they complement the theme of the show?; which songs do you leave in or out? People can be tentative and sometimes quite nervous about having their works judged by others. Our role as artists is to bring our own expertise into these projects by helping shape the material and asking the right questions to people who often have not experienced this before. The key to all of this is to create open and authentic negotiation in an environment where trust is paramount.

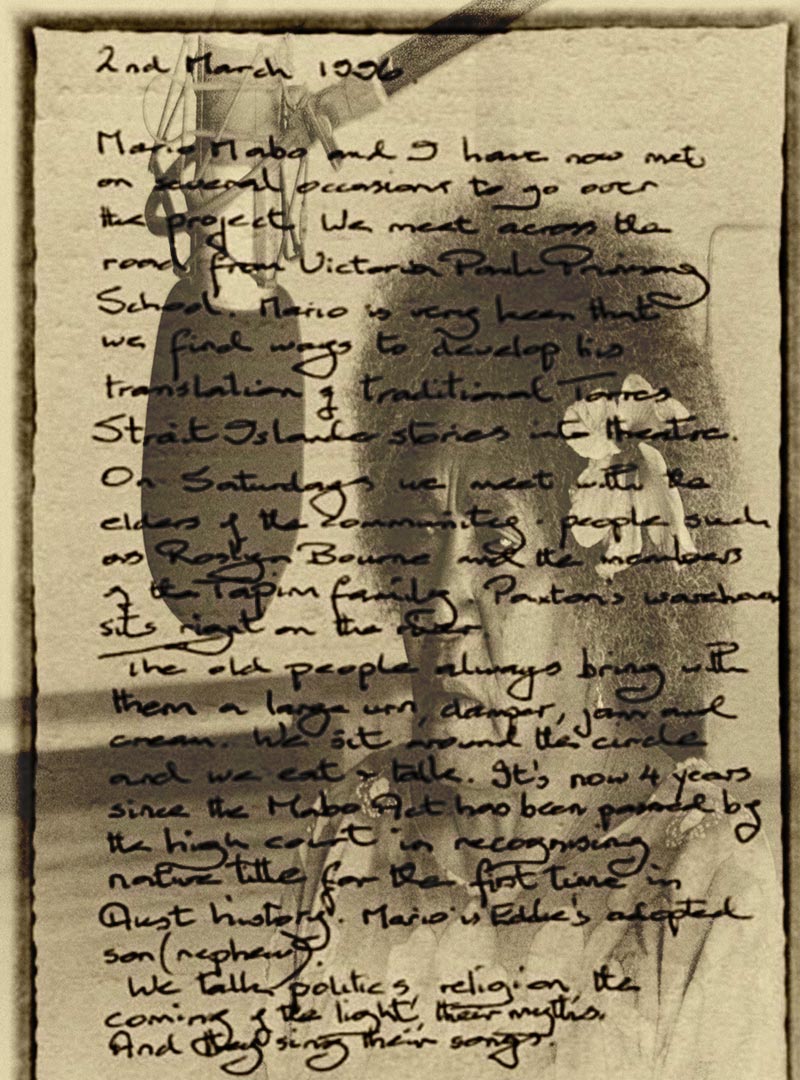

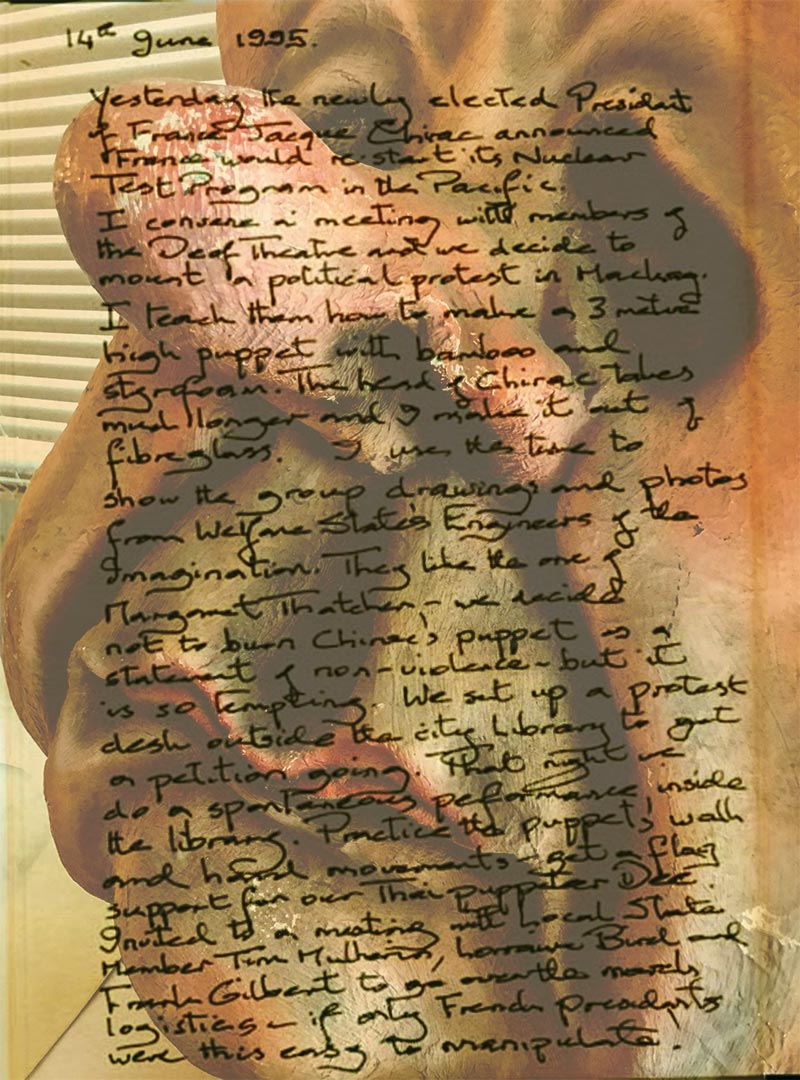

There are exceptions, particularly if the outcome is driven too quickly at the expense of creative detail, production values or in some cases cultural sensitivities. Sometimes it can be a case where you and the participants negotiate and decide not to create the outcome. In 1996 I was invited by Mario Mabo to work with him and families from the Torres Strait Islander community on adapting Mario’s translated children’s stories to the stage. Here I was as a privileged white fella working with Torres Strait Islanders who throughout the past 200 years had been exploited and dispossessed of their land by a colonial regime. The context of that political, cultural, economic and social history stayed with me throughout the whole project.

We met every weekend at Paxton’s Warehouse on the river. The old people always bought with them a large urn, damper, jam and cream. We sat around in a circle and we talked and we ate. This was 4 years after the Mabo act had been passed by the High Court in recognising native title for the first time in Australian history. We talked politics, religion, the coming of the light, their myths, and children stories. And they sang their songs. Mario led the workshops. This went on for weeks. On a number of occasions when I saw an opportunity I leaned across to Mario and suggested we try a drama game or role play some of the stories. “All in good time Steve” was Mario’s reply. We never performed those stories. There was no theatre outcome. We all decided it was not the right time. I was frustrated. The question of whether I would have to give back the funding or whether I would get funding again was part of that frustration. It took me a while to realise that I was actually privileged to be part of that process and those conversations.

The islanders had a strong sense of who they were and they understood their history and the history of colonisation and the effects it had on their culture. This was a lesson I was to take with me when I worked in India, Vanuatu, Minyeri Remote Community in Arnhem Land and in Japan. You cannot simply walk into a community and ignore the history of colonisation and your privileged place in that context. My preconceived ideas of the Torres Strait Islander community had been changed. I got to know people in the Mackay community who were from the Torres Strait Islands. And they got to know me. Pretty good outcome for a first encounter I thought. And when I walked down Victoria Street past the Tapim family tent outside the newsagency, Ringo and Ace Tapim , Millie Benefather and Roslyn Bourne always went out of their way to say hello. The right time came 10 years later. In 2006, Mackay was chosen as the town to host the National Regional Arts Conference. Not only were we able to bring elders and youth from the Torres Strait Islander community together but the Aboriginal and Australian South Sea Islander community joined us in a dance project called No2Stones. More importantly I was able to facilitate the employment of several key artists from each of the communities to lead the project.

What our Peers and Critics said:

“Groundbreaking in process and performance. No 2 Stones has changed the face of relationships between Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Australian South Sea Islander communities in Mackay forever.”

Janice Quadrio. Regional Arts Australia Case Study“They were like brothers and sisters on that Saturday. They respected and acknowledged each other as cultural leaders with no line in the sand. This spoke to performers in a deep way. I felt privileged to be involved.”

Mulum Stone. Indigenous Cultural Development Officer. Mackay Regional CouncilMemory- Timesips

When Kyla Ranger and I sat down with a resident at an aged care centre, they would often talk about their past. In some cases these chats soon led to recordings which then became memorabilia for family members and on some occasions formed part of multi media presentations during meals in the centre’s dining area. When other residents heard the stories they discovered that the lady in room 205 was Pat Tomachi, who was once a blacksmith and a female jockey from Newcastle.

Images: Top left: Julie Timor telling her story to Steve Mayer-Miller ; Top Right: Pat Tomachi telling her story to Kyla Ranger

Bottom: Pat Tomachi in Newcastle ;

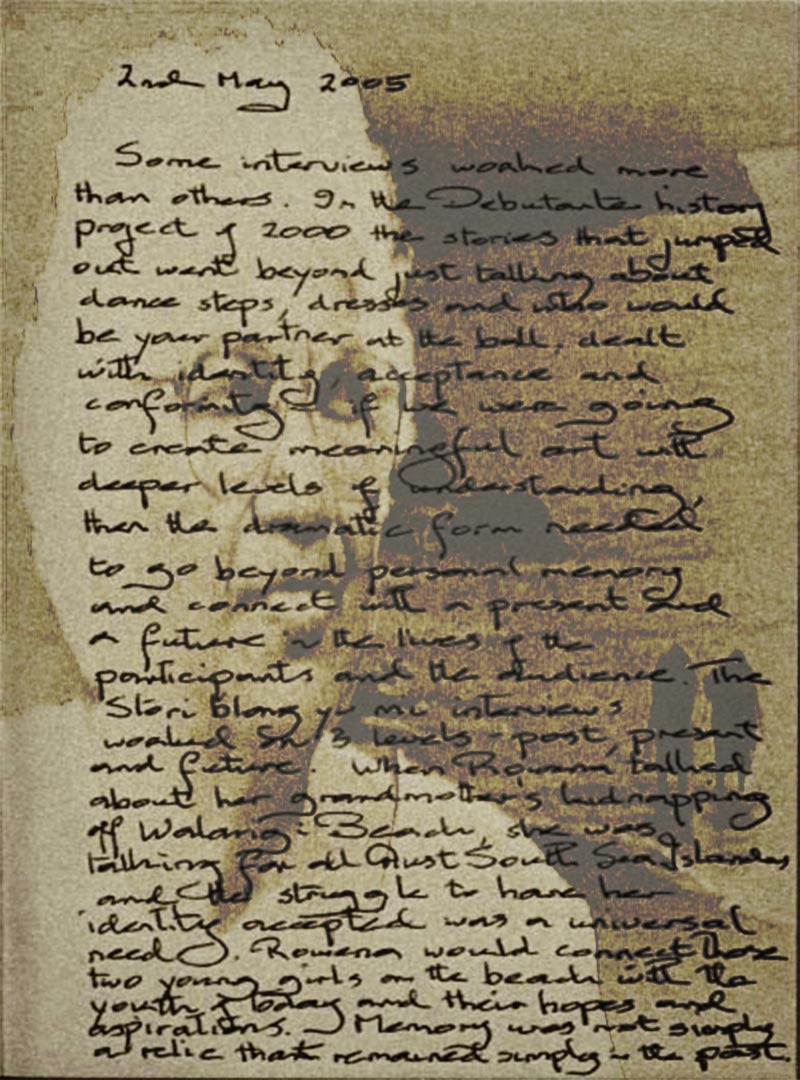

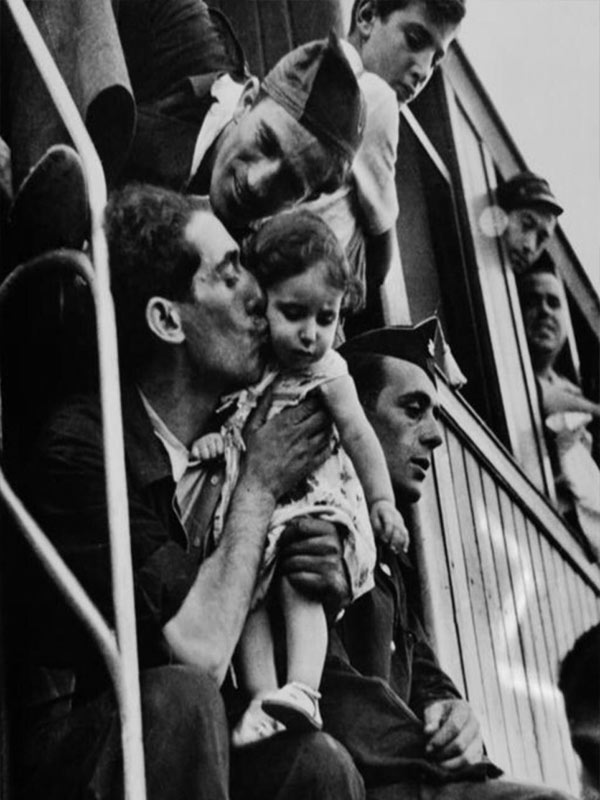

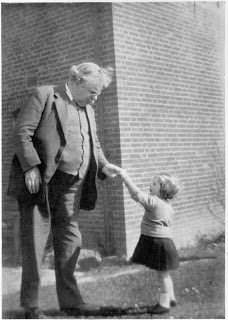

One person’s memory of events in their life can sometimes trigger similar stories in other people’s lives. The interviews I did with Maureen Costello from Homefield Dementia Unit and Elfrieda Mayer a retiree who lived at home, made a connection that went beyond the past and private . Both had been children, living in large cities during World War 11. Both had vivid memories of air raids. Maureen was in Southhampton during the blitz and remembers lying in her family’s homemade backyard bomb shelter when bombs from the German Luftwaffe landed in her street destroying homes and killing people. Elfrieda lived at 44 Hahngasse in Vienna with her mother, brother and grandmother. She remembers the sound of the air raid sirens and the roar of American and British planes overhead. At times on her way home from school, alone, 9 year old Elfrieda would have to run to a public air raid shelter during a raid. Both these stories became quite poignant for me when I watched Japanese primary school students in Sendai practice air raid drills following the launch of a North Korean missile in October 2017 . It flew over the northern island of Hokaido. The warning siren sounded on my mobile phone at 6.50am while I lay in bed in my apartment in Sendai. Air raid shelters were suddenly not a thing of the past. In many of these projects we would finish up in a place where we did not expect to go – led on by the people’s stories. In Gladstone we began a group discussion about people’s memories of dancing. It took a little while to get the discussion going. Joan talked about how as a young girl she would take off her shoes and dance in the dirt. Hazel responded by telling us that shoes were a central part of her life. She ran a shoe shop in Toowoomba. Very soon the discussion focused on people’s stories of shoes. Everyone had a story. It reminded me of the importance of leaving space for a group of people to chart their own direction and also the importance of a facilitator to point out the strengths of certain stories and stay with them, mining them for their riches. There were times when personal history outcomes were not appropriate. Sometimes the person telling the story only wanted you to know. Keeping that trust was important. Some residents were worried they may get the facts wrong and their families might be embarrassed. I began to explore other ways of engaging residents without relying on memory: Dance, Music and Timeslips. . Our job is to shape these experiences into forms Robert Jefferey… CASE STUDIES Pat’s Story: https://vimeo.com/95706256 Robert Jeffery: https://vimeo.com/63494104

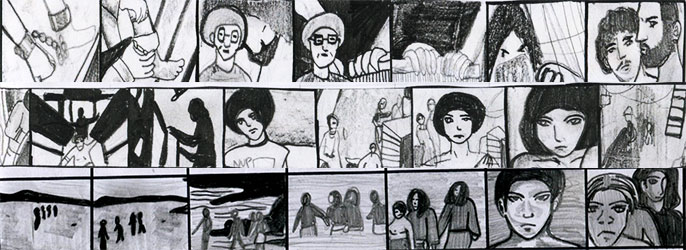

Timeslips

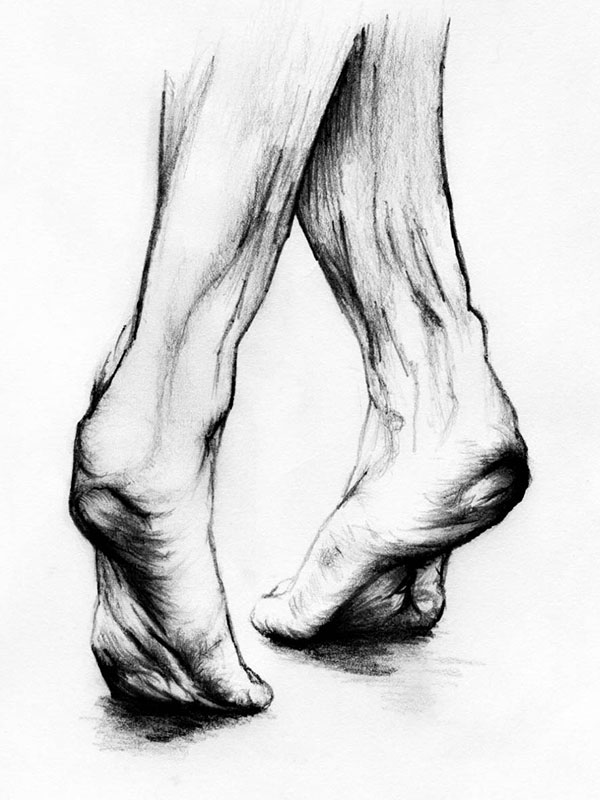

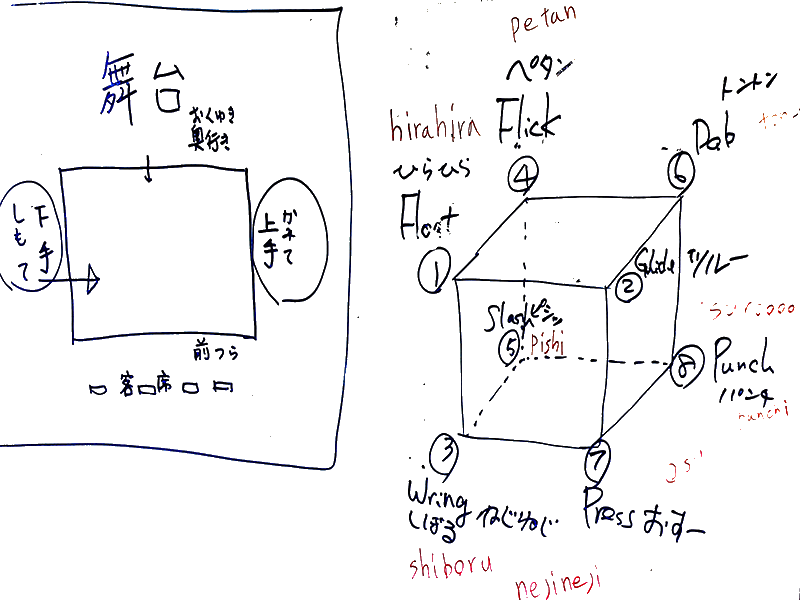

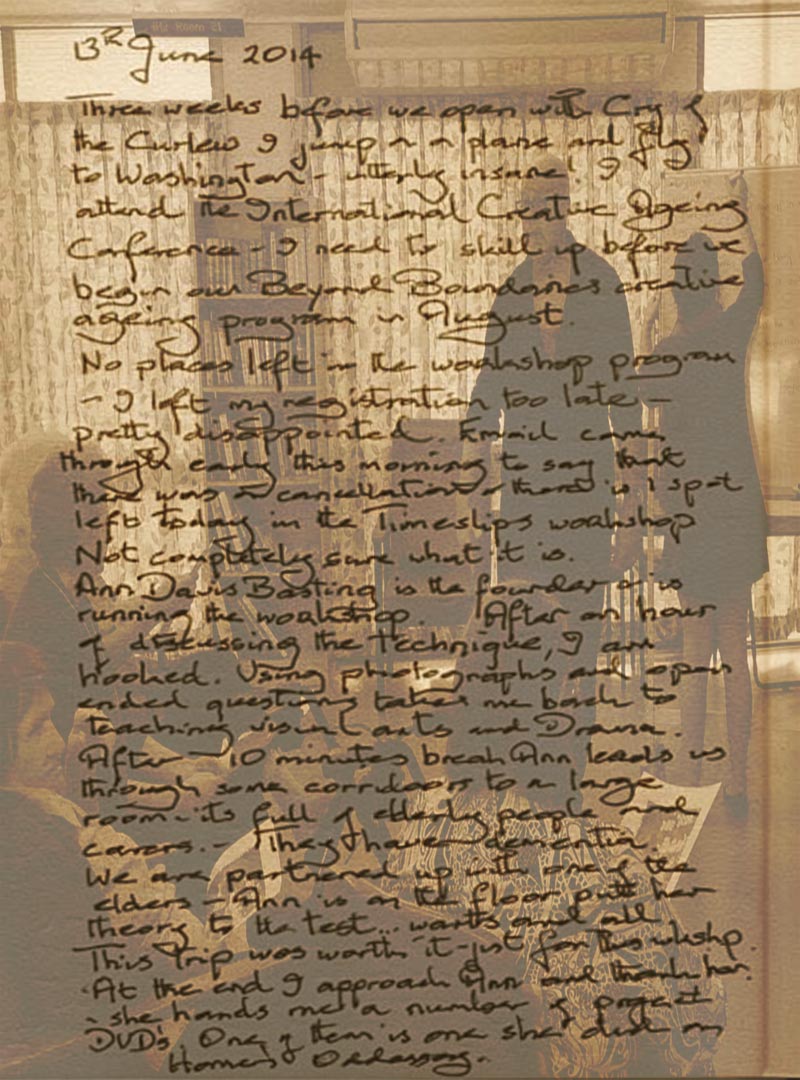

I was first introduced to Timeslips by it’s author Dr Anne Bastings during a workshop she gave at the International Creative Ageing Conference in Washington in 2014. Timeslips is a form of storytelling that involves small groups of residents responding to open ended questions around a photo or a painting that serves as the basis for the story. Three people help facilitate the exercise: A questioner who asks open ended questions, a scribe who writes all of the responses often on a whiteboard for all to see, without editing, censorship or the need for grammatical correction; and a person to wander the floor listening for those responses that may not have been picked up by the scribe. From the start it is made clear to the residents that there are no incorrect answers. All responses are recorded. It did not matter if one person’s response conflicted with another. All stories have differing points of view. Every few lines we would stop and read out the responses to maintain the group’s focus. When the story was complete we would read it out again and ask for a title. At times the story would sound like free form poetry. At the end we collected people’s names and by the next morning we had typed up the story with the picture, all the names of the authors and framed it and presented it to them to be hung up in a central place in the home. I loved it. When people realised that all their responses would be accepted, it freed them up. They no longer had that worry of “failure” of being judged “incorrect” because they couldn’t remember something or what they remembered did not align to Wikipedia. It reminded me of Keith Johnstone’s Improvisation methods of creating an environment in a theatre workshop that gives people permission to say things and do things spontaneously without fear of failing. As an extension to the writing of the story we began to experiment with movement and gesture . The residents that we worked with in Mackay, Winton, Gladstone, Biloela, Longreach and Mt Isa all took to it as did the staff who saw another side to the residents. It was creative and highly imaginative where you were in the moment waiting to hear where the next line would take you. In 2015 we drove 4000 kilometres from Mackay to Mt Isa and back working with over 200 new Queensland authors.

Participation